|

|

|

|

|

Home →

Publications →

Mother Earth News

|

|

Mother Earth News

Issue #110: The Tom Brown School (Wilderness Skills

Schools Part 3),

by Terry Krautwurst, pg50 (Mar-Apr 1988) |

|

|

|

A short course

in tracking, nature and wilderness

survival

I'm standing at the upper edge of an

overgrown hillside, a few sloping acres of knee-high grasses

and brush in rural western New Jersey. Above, half a dozen

raucous crows play in a blue sky—the definitive blue sky,

cloudless, crystal clear. Along the lower edge of the field

huge oaks and willows rise above lesser foliage, their boughs

arcing over a wide river, dappling the water in leafy shadow.

A typical countryside scene—unless you

include the 40 or so human posteriors and pairs of legs

grazing in groups scattered across the field. The bodies to

which they're connected are thrust out of sight into bushes

and briars and grasses, heads hidden like—well, no, not a bit

like ostrich heads hidden in the sand. Hardly evading the

world, these people are deep in discovering it.

This is the next-to-last day of a six-day

Standard (introductory) course at the Tom Brown School of

Tracking, Nature and Wilderness Survival. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

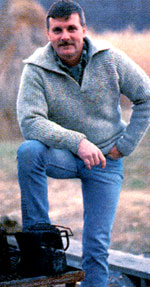

"The

Tracker" (above) stresses outdoor skills and respect for

the wild. Here he helps advanced students learn atlati

throwing (below) and select river stones for primitive

tool making. |

|

|

|

|

|

An excited voice emerges from somewhere

in a clump of sedge. "Tom! I found something! I think it's a

weasel hair!" A hand pops up, then a head. "Wow, look at

this!" another voice, belonging to a bluejeaned backside,

shouts. "Hey, I think I found a sleeping chamber!" someone

else hollers. "Look at all these trails!" an awed voice

exclaims, its legs snaking deeper into the vegetation.

The excitement of discovery is

contagious, and, dropping to my knees, I gladly shed my role

as observer/journalist, part a layer of matted grass, poke my

head downward and join my fellow students in a heretofore

unseen world. "I'll be damned," I whisper to myself as I

immediately uncover a tiny, wellworn path—too small for

rabbits, probably a vole run—winding around a sapling and

meandering downhill. "Would you look at that."

Belly down, nose inches from the ground,

I study the two-inch-wide trail, a Lilliputian highway paved

with grass pummeled smooth by countless wee footsteps. The

closer I look, the more I am drawn into life in this grass

forest, and the more I see: some droppings here, a hair there,

some tiny scratch marks, a rounded, nestlike chamber.

Carefully replacing the thatch above one section before

parting the vegetation over the next—as our instructors have

repeatedly reminded us to do—I trace the tunnel downhill.

Every few feet it intersects other paths, some hidden, some

exposed, some larger, some smaller—roads traveled by mice,

deer, foxes, ground hogs, raccoons. Together, I realize, they

form an amazing network, a sort of macrovascular system

pulsing with animal movement, that must cover the entire

field, and—good Lord, think of it—all the fields adjoining

this one, and all those adjoining them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gigging dinner with a homemade spear; a skill for

expert adventurers. |

|

|

|

|

|

Transfixed, I slither further into the underbrush.

Some minutes later, a sonorous voice

breaks the spell. "OK, people, gather round." I stand up,

blinking in the sunlight, in time to see my fellow students

emerge, heads popping up through the vegetation one by one,

like surfacing scuba divers. We assemble around our mentor,

Tom Brown, Jr., himself.

At 37, Brown is a teacher, author and

living legend. He looks the part. Over six feet tall, he

stands ramrod straight, a blue T-shirt stretched across a

broad chest and powerful biceps. His hair, showing streaks of

silvergray, is cut short, military style—a far cry from the

flowing tresses he has worn until only a few months ago. His

eyes are steel blue, piercing, always darting, never focusing

for long on any one person or thing.

Brown became a national figure in 1976,

when his first book, The Tracker, was published. The Tracker

tells the extraordinary story of Brown's childhood, spent

in the New Jersey Pine Barrens under the tutelage of an

elderly displaced Apache scout named Stalking Wolf. From the

time he was seven years old, he was trained by Stalking Wolf

in the old ways, the traditional skills and philosophies of

Native Americans. Brown believes, in retrospect, that he was

chosen by Stalking Wolf to pass along the ancient teachings

and skills.

In 1977 he started this school, today

probably the best-known and largest wilderness survival and

tracking school in the country. He has also written a set of

field guides, a second autobiographical book, The Search (a third is in the works), and

countless magazine articles, including a popular series, "At

Home in the Wilderness," for MOTHER.

But even before he started the school or

wrote his first book, Brown was known among law enforcement

and government agencies as "The Tracker." His exploits in

finding criminals and lost children, sometimes staying on the

trail without provisions for days, are epic. He is widely

acknowledged as

the best tracker in the country, period.

This week, though, he is our teacher, our

medicine man, our Stalking Wolf.

Brown gestures with a sweep of his arm to

the field and meadows adjoining. "People travel hundreds of

miles to crowd into places like Yosemite or Yellowstone to see

the wildlife," he says, "when there's so much to see and

appreciate right in their own back yards. A field like this

contains every bit as much wildlife, every bit as much natural

diversity and variety, as any park anywhere in the country.

And all you have to do is learn how to look for it. That's

all. Just learn how to look and see."

We have spent countless hours this week

doing just that, and a great deal more. In five days of

almost nonstop lectures and workshops—beginning at 8:00 each

morning and continuing into the night, sometimes past

midnight—we've covered an astonishing variety of skills, each

in depth: making fires, building shelters, finding water,

building traps and snares, skinning and tanning, making

natural cordage, cooking, arrow and bow making, flint

knapping, Eolithic rockwork, stalking, foraging, hunting

and—of course—tracking.

"I pack this course with information, and

then I pack it further," Brown told us the first night. "Time

is critical here. I use every minute. When you're done on

Sunday and you look at how much we've gone over, your head

will reel."

My head's been reeling since the second

day. I've filled two notebooks with lecture notes and I'm

working on another. My hands are scratched and calloused from

workshops: from carving traps, twisting plant fiber to make

cord, chipping rock into cutting tools.

After lunch, each student uses the time

remaining before the next class to practice skills or complete

projects started earlier. An options trader from Brooklyn

pulls a nearly completed bone arrowhead from his pocket and

begins scraping it across a piece of rock to give it a keen

edge. In the field beyond the cooking area, three students—a

real estate salesman, a machinist and a physical therapist—set

chunks of firewood on end in a line as targets, move back 30

feet and practice throwing a rabbit stick, an arm-length,

wrist-thick piece of tree limb that, when hurled correctly, is

a deadly accurate survival weapon for hunting small game.

Over by an outbuilding another student

stands staring straight ahead, arms outstretched to either

side, wiggling his fingers slightly. It's an exercise in

stimulating peripheral vision, an element, Brown says,

essential to increasing your awareness of the world. He has

taught us to widen our vision and avoid fixing our eyes in any

one direction for long—a technique he calls "splatter vision."

"Always be a tourist," he says. "Look at the room you're in,

the street you're on, the trail you're walking, as if you were

seeing it for the first time—no matter how many times you've

seen it before. Your mind always seeks the familiar, but you

miss so much. Vary your vision. Refuse to let your

eyes focus on the same things you always look at. Force

yourself to look in different places. Wherever your vision

goes, your senses go."

Other students are at the edge of a

cornfield, practicing the graceful, excruciatingly slow

movements we've learned for stalking. Still another is down on

all fours, notebook at side, imitating the basic animal

walking motions Brown has taught us. "You can't track an

animal if you don't understand how it moves," he says.

A shrill squeaking sound—wood rubbing

against wood—comes from behind me, and I cringe. I don't have

to look to know that it's a student working a bow drill, the

basic survival fire-starting apparatus consisting of a notched

fireboard, a dowellike spindle, a handhold, a small bow and a

tinder bundle. Making one, then starting a fire with it, was

our first workshop. In typical Brown fashion, we were provided

a chunk of cedar, the least desirable of acceptable woods. "If

you can get a bow drill fire going with cedar," Brown says,

"you can get one going with any of the better woods."

I'm embarrassed to be one of the few

students who have yet to succeed. I sigh. What the heck, I'll

try again. I get the drill I've made. I fluff up the tinder

bundle and lay it on the floor, place the fireboard over it,

wrap the bow's cord around the spindle, position the spindle's

bottom end on the board, put the handhold on the top end.

OK. Left foot anchors the fireboard.

Right knee behind left foot. Chest down tight against thigh,

left arm braced across shin. Start sawing with the bow, easy

at first, back and forth. Now pick up a little speed. Back and

forth, back and forth. Faster. Push down harder on the

spindle. There, some smoke. A little faster, bear down a

little harder (I'm running out of breath, my arm's cramping).

More smoke. Good, faster now, faster; push down a little

harder . . . pop, clatter . . . the spindle flies off the

board and across the room, just as it has countless times

before. Feeling beaten, I walk over and pick the spindle up,

forgetting that the end is hot, and burn my hand—injury added

to insult.

Just then Frank, one of the school's

instructors, comes around the corner. "Did you get your fire

yet?" he asks jovially. I grimace. "Look," he says, "let's get

together after tonight's lecture and see if we can't

figure out what you're doing wrong."

"Nah, thanks, that's OK," I

say, shrugging. "I'll just practice when I get home. It's not

that important, no big deal."

I lie.

The afternoon's tracking lecture, like

those before it, is electrifying. When Brown talks tracking,

his voice shakes with excitement, his eyes burn with

intensity, he paces back and forth, his hand flies across the

blackboard to illustrate a point. He is obsessed with tracking

and admits it. As a child, he developed a callus across his

lower chest from spending so much time crawling on the ground

poring over tracks.

"Every mark is a track," Brown teaches.

"Everything that is not flat is a track; the Grand Canyon is a

water track, a fallen tree is a track of the heartrot that

killed it and of the wind that felled it. Every dent, pocket,

fissure, scrape, mark in the ground, every rolling hill, every

scratch is a track. The ground is a manuscript, an open book;

it is littered with tracks, from the largest to the smallest,

and each one tells you something."

To me, the lectures are a revelation.

Brown's teaching goes way beyond merely identifying foot or

paw prints in the dirt. "Earth mother gives you a clear print

to follow maybe 5% of the time," he says. He teaches us

compression tracking—identifying vague depressions in the

ground or deep leaf litter or thin dust by their general shape

and the patterns in which they're arranged.

Then he moves to an even more subtle art,

the reading of what Brown calls pressure releases, the

characteristic ways the earth compresses, cracks, crumbles,

moves, responds to a foot or paw. There are hundreds of them,

and each means something different. There is a single release

that indicates an increase in speed from slow jog to jog,

another for a slight turn of the head to the right, another

for a momentary hesitation (perhaps the person or animal

considered changing direction for an instant, then decided

otherwise). Pressure releases tell all.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

leaf hut is one of the simplest to construct, yet most

effective, emergency shelters. It offers a warm, dry

temporary home for the lost hunter or

hiker. |

|

|

|

|

"From one footprint," says Brown, "I can

tell a person's height and weight, gender, emotional state,

condition of health and degree of strength. I can tell whether

they're right- or left-handed, whether their stomach is full

or empty, whether they have to go to the bathroom. I can even

tell a few days before a person gets a cold, because there's a

restriction in breathing."

The lecture lasts well into the evening.

Brown's energy never abates. He draws dozens of release

patterns on the blackboard. He steps into a tracking box—sort

of a pro quality sandbox—and demonstrates how even subtle body

movements are revealed in prints. He is unrelenting. He

sketches more releases. He tells us of releases within

releases, of microreleases. We learn that all of the releases

we've discussed can be created not only by a foot or paw, but

by individual toes, by each lobe of an animal's heel pad.

It's simply too much for a mortal to

absorb. By the time we file out, I've filled my third notebook

and I'm brain dead, the victim of a tracking fanatic. I take

advantage of a rare lull in activities and tumble into my

sleeping bag.

Later that evening, an hour before we're

scheduled to partake in a traditional sweat lodge ceremony—a

culmination of the week's lessons—I walk into the wrong room

at the wrong time. A half dozen students are standing in a

loose circle cheering, and in the center a student who hadn't

yet managed to get a bow drill fire going is holding a flaming

tinder bundle.

They see me before I can back away. "OK,

Terry, you're next! You can do it! You've got to do it! Think

fire! Think fire!" Before I know it, I'm in the one place in

the world I least want to be, kneeling over a cold, hard

fireboard, bow in hand.

I start sawing away, back and forth, back

and forth. There's a wisp of smoke. I saw faster. More smoke.

"Go! Go!" the people in the background are chanting. I push

down harder, saw faster. A little more smoke. Back and forth,

back and forth, for what seems an eternity. Suddenly the smoke

billows and someone shouts, "You've got a coal, you've

got a coal!" I drop the bow, grab a toothpick-size twig

and gently nudge the coal into the tinder bundle. Carefully, I

pick up the bundle, cradle the coal inside the fibers and

bring the tinder to my lips. I blow gently. The coal glows

red, the tinder smokes. I blow again. It glows redder. I blow

again. The coal turns bright orange—and dies. A groan goes up

from the cheering section.

But I know what I've done wrong, and I'm

already sawing away again by the time my coaches are telling

me: "Feed the coal! You've got to keep the tinder all around

the coal!" The smoke billows again, I get a coal again, I tip

it into the tinder and bring the bundle to my lips again. I

fill my lungs with air and blow it out, long and steady. The

coal burns orange. I press the tinder inward, take another

breath, blow it out. More burn, more smoke. I keep the rhythm

going. Breathe in, blow out, more tinder, breathe in, blow

out. The smoke thickens and someone whispers, "He's got it,

he's got it." Breathe in, blow out, breathe in, blow-whoosh!

The bundle bursts into flames!

I am no shouter; at football games, a

muttered "All right" is the most I can manage when the home

team makes a touchdown. But at the sight of that fire, that

astonishing flame created from nothing, something way down

inside of me wells up and before I can catch myself I'm

standing and shrieking like a banshee, announcing with a

triumphant primal scream that I've made fire.

It is a night for profound experiences.

In the sweat lodge, there is no light, and in the darkness no

up or down, no sense of space or time. There is only the

heat—intense, purifying, drawing water from our bodies—and the

rhythm of our breathing, of Brown's voice chanting, of ebb and

flow. "Every drop of water contains a little bit of the

ocean," Brown has told us. "In the sweat lodge you can feel

the ancient pull of the tide, reminding you of your origins

and of the unity of all life."

We emerge from the lodge into a cold,

bright, crystalline night. I stand under the stars, throw my

head back to the sky and bask.

By 9:00 the next morning we're on our

hands and knees out in front of the barn with Brown, tracking

mice across the farm's hardpacked gravel driveway. I can't see

the tracks Brown points out until I heed his instructions:

"Always keep the track between you and the light, get close to

the ground, and look at the surface at a severe angle." I lean

way down, my eye an inch or two above the ground, low morning

sun opposite. There; so subtle they're barely more than a

reflection, the crucifix-like compression shapes

characteristic of rodents.

An hour later we're back in the

classroom. Most of us have to leave soon. "I have a confession

to make," Brown says. "I brought you here on false pretenses.

You came here to learn survival skills, and I've taught you

those skills. I know that with what you've learned you'll be

able to survive, quite comfortably, anywhere in the country as

long as it's not a parking lot. But that's not why I spent

this week with you." He pauses. His voice shakes with emotion.

"I believe we're fighting a desperate war to save what's left

of the earth from destruction. The earth is our mother. She is

lying raped and dying by the side of the road. She needs our

help. We have to help, or she'll die, and we with her.

"I believe that teaching survival gets to

people's hearts, that when a person learns how to enter the

world purely, unencumbered by society, where you live a

hand-to-mouth existence with the earth, a connection develops.

That's why I run this school, to bring as many people as

possible back to the earth, and to send them out to teach

other people."

Brown speaks slowly, pleadingly. "I hope

that when you go home you will have a new love and respect for

the earth, that you will have a commitment to help save it,

and that you will help bring others back close to the earth.

Please, people, take what you have learned here this week and

teach others. Time is running out."

The room is silent, charged with passion

and purpose.

By late afternoon, I'm on a crowded bus

headed back to the Newark Airport, Brown's words still ringing

in my ears. I'm leaving the school with far more than I

expected.

Am I an expert tracker? No, that'll take

time. But I've got an awfully good start. I've acquired

survival skills that I know will keep me alive should I ever

need them, and that in any case will allow me to hike, camp or

otherwise enter the natural world free of worry, free of what

Brown calls the "what if" question: What if I lose my

backpack, what if I break my leg . . . And I'll be able to

teach those same skills to my wife and children and friends.

Most important, though, I've gained a

greater sense of my place in the world and a heightened

awareness of the life around me. I have begun, in a small way,

to feel what the Native Americans called "the spirit that

moves in all things."

The bus pulls into the Newark Airport, a

hubbub of concrete and cars. It has been quite a week.

|

|

|

|

|

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

|

|

|

|

|

|