|

I, Nature Boy

Outdoor magazine, October 2000

For PDF format click here

And other divinations from Tom Brown's Tracking, Nature, and

Wilderness Survival School. As told by David Rakoff—Acolyte of the

Standard Class, Master Bowdriller, Sweat Lodge Scaredy-Cat, and Friend to the

Vole Photographs By Charles Gullung

IT IS DIFFICULT in the extreme to construct either a Figure-Four

or Paiute deadfall trap, to say nothing of having them work, in the dark, and in

the rain, at 11 p.m., after 17 hours of lectures and demonstrations, during

which one has already been taught (among other things) the Sacred Order of

Survival—shelter, water, fire, food; how to make rope and cordage from plant

and animal fibers; how to start a fire using a bowdrill; finding suitable

materials for tinder (making sure to avoid the very fluffy and flammable mouse

nest as it may contain hanta virus); how to recognize the signs of progressive

dehydration; how to make a crude filter out of a matted clump of grass; how to

distinguish between the common, water-rich grapevine and the very similar yet

very poisonous Canadian moonseed; how to make a solar still out of a hole

covered with a sheet of plastic (and how to continue the condensation process by

urinating around the hole); and the Apache tradition of honoring those things

one hunts, be they animal, vegetable, or mineral. All of this within the first

day and a half of a Standard Class session at Tom Brown's Tracking, Nature, and

Wilderness Survival School in the wilds of northwestern New Jersey.

|

|

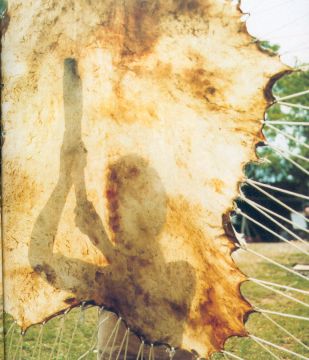

A student prepares to stalk prey by "de-scenting" and muddying

up his body to "look like a shadow." |

The Standard is the first and most basic of 28 classes offered by the school,

a Wilderness 101 of sorts—a weeklong, lecture-heavy, intensive introduction to

primitive outdoor skills and nature awareness. The same skills and awareness

found at the very heart of the bildungsroman that is the oft-told life story of

Tom Brown Jr. Briefly, the story is as follows: Growing up in the Jersey Pine

Barrens in the late 1950s, a young Tom spends almost every waking moment from

the ages of seven to 18 in the woods under the tutelage of his best friend

Rick's grandfather, Stalking Wolf, a Southern Lipan Apache from Texas. Brown's

apprenticeship ends in 1967 upon his graduation from Toms River High School. He

is designated 4-F by the draft board due to a chip of obsidian that had lodged

in his right eye in his teens; years earlier, Stalking Wolf is said to have

predicted that a "black rock" would keep the boy out of Vietnam. Over

the next decade Brown takes odd jobs to make the money necessary to spend his

summers testing his skills in unfamiliar environments across the country (the

Tetons, the Dakota Badlands, Death Valley, and the Grand Canyon), living in

debris huts and scout pits of his own devising, and subsisting on food he

forages or kills himself. Eventually the young man re-emerges into society with

a single-minded mission: to teach others and lead them back to the woods and a

love of nature.

There have been digressions along the way. Brown has trained Navy SEALS in

high-speed invisible survival and helped the FBI and state law enforcement

agencies in tracking persons both missing and criminal. He solved his 600th case

on his 27th birthday, a full year before the publication of his first book in

1978. The Tracker is a tale of an adventurous boyhood of limitless

self-reliance in an unfathomably Arcadian wilderness. It makes for compelling,

if not always easy to swallow, reading: part Richard Halliburton, part Carlos

Castaneda, part Kung Fu. Grandfather, already an octogenarian in 1957

when Tom first meets him, appears as a man of almost Buddhalike wisdom with a

penchant for posing oblique, seemingly insoluble riddles and laughing discreetly

behind his hand as Rick and Tom, mired in narrow Western thought, fumble for

answers.

It might not be Thoreau, but it is the key to the legend that Tom Brown may

very well one day become, and certainly already is here at the Tracker School.

Brown, 50, is a cultfigure of international stature. The best-selling author of

16 books, whatever tracking Brown does now, be it for the crooked or the merely

lost, is more of the armchair variety. Having trained tens of thousands of

people at his school, he can call upon a global network of former and current

acolytes when his tracking wisdom is requested.

Many of us here for the Standard—some 90 people from the United States and

Canada, four from Austria, and a young woman all the way from Japan—are

aspirants, yearning to join those ranks of expert trackers. Everyone is

acquainted with Stalking Wolf. All have read at least part of Brown's oeuvre, be

it one of the field guides to wilderness survival or to wild edible and

medicinal plants, or perhaps the more spiritually oriented titles, such as The

Vision, The Quest, The Journey, or Grandfather.

According to the school's statistics, roughly 90 percent of us will return to

take a more advanced course, starting with the Advanced Standard and branching

off thereafter, perhaps to learn Search and Rescue, the Way of the Coyote,

Intensive Tracking, or How to Be a Shadow Scout.

We are diverse in age and gender, and we run the gamut from the pragmatic to

the ethereal; from the unbelievably sweet 18-year-old vegan boy from Portland,

Oregon, to the gun enthusiast who brought his own supply of hermetically sealed

decommissioned military MREs ("Bought 'em on eBay for ten cents on the

dollar after the whole Y2K thing didn't pan out. Best au gratin potatoes I ever

ate"); from the congenial soi-disant "hillbilly from West

Virginia" in his fifties to the twentysomething physics major looking to

drop out for a while. Most are friendly, intelligent, and environmentally and

socially committed. More than a few are involved in education, in particular

working with troubled teens in the wilderness. And, I am relieved to see, most

are refreshingly immune to the pornography of gear. They radiate good health as

they unpack bags of gorp, apples, whole-wheat pitas, and huge water bottles. I,

too, have come prepared—with a deli-size Poland Spring mineral water, assorted

candy bars, and four packs of Marlboro Lights.

I ARRIVE ON APRIL 30, a beautiful, sunny, but very windy Sunday

afternoon. We all spend the first few hours battling the strong breeze to pitch

our tents, the placement of which is overseen by Indigo, one of the eight or so

volunteers, alumni of previous Standard Classes, who help out for the week and

in so doing refresh their skills and relive what was clearly for them a

wonderful experience. Indigo, a rural New Jersey local, hovers somewhere between

50 and 70 years old. With her sun-burnished face, craggy features, and rather

extreme take-charge demeanor, she is straight out of My Antonia. Still,

she's not unfriendly, even as she tells one of the Austrians, his tent staked

down and ready, "Uh-uh, mister. You gotta move it about four inches that

way. We're making a lane right here." Indigo gesticulates like an urban

planner dreaming of a freeway; she is the Robert Moses of Tent City.

|

|

|

The indomitable instructor Ruth Ann Colby Martin

practices self-sufficiency in a debris hut |

|

|

|

|

Tanning a deer hide |

|

It should be noted that we are not actually in the Pine Barrens, sacrosanct

locus of Brown's childhood in and around the town of Toms River. The Standard

Class is held on the Tracker farm in Asbury, New Jersey, near the Pennsylvania

border (not to be confused with Asbury Park, sacrosanct locus of the early

career of that other South Jersey legend, Bruce Springsteen). Brown splits his

time between here and the Barrens, but the farm at Asbury is better for teaching

novices because of its rich biodiversity; the surrounding fields, meadows, and

light forest, and the Musconetcong River, which flows a few hundred yards away,

offer ample flora and fauna for this week of instruction. Aside from the barn,

the central structure where the (hours upon hours of) lectures take place, the

farm consists of Tom Brown's house, a dozen or so portable toilets, and a

toolshed with an awning under which sits a row of chuck-wagon gas rings—our

cafeteria. All activity is centered around the main yard, a scant acre of patchy

lawn that lies between our nylon sleeping quarters and the barn. In the center

of this is the all-important fire, which burns day and night, heating a large

square iron tank with a tap, where we get hot water for our bucket showers.

Brown used to teach the Standard from beginning to end himself. These days,

aside from evening and morning talks, he leaves the teaching responsibilities to

his paid instructors, the most organically charming group of people I've ever

encountered. They're all affable, pedagogically gifted—there isn't a dud

public speaker in the bunch—and chasteningly competent at the endless variety

of primitive skills we're here to learn. They're a lovable crew of commandos

straight out of central casting: Kevin Reeve, 44, director of the school, a John

Goodman paterfamilias type who opted for early retirement from Apple Computer

nine years ago after taking his Standard Class; Joe Lau, 31, resident flint-knapper—his

stone tools are things of beauty—currently ranked second in ninjutsu in the

state of New Jersey; Mark Tollefson, 32, plant expert, wild-edible savant, also

in charge of food; Tom McElroy as the Kid—at 23, youth personified—a

thatch-haired Tom Sawyer with an aw-shucks charm that belies his sniper's aim

with the throwing stick; and Ruth Ann Colby Martin, 26, resident Earth Mother,

who, it seems, can do literally everything, and is polymathically, beatifically

dexterous, capable, strong, beautiful, and funny—Joni Mitchell as Valkyrie.

Even though Ruth Ann has already run the Sandy Hook marathon on the day we meet

her, she fairly glows. Let me be clear: As an avowed homosexual, I make it a

practice to seek out the amorous embraces of men over those of women, and yet I

fall heavily for Ruth Ann.

That first evening, the entire class gathers in the barn for an orientation

session in which we are advised of the school's general guidelines and given our

first taste of the ethos of the place, summed up by Kevin pointing to a sign

above the stage. It reads, "No Sniveling."

"This is a survival school, not a pampering school," Kevin adds. As

if on cue to reiterate the rustic authenticity of the place, a bat that lives in

the barn swoops down over our heads. We are reminded to hydrate regularly and

properly, and to beware the poison ivy that grows rampant on the farm. "And

if you are taking any sort of medication to regulate your moods," Joe tells

us, "we request that you stay on that medication while you're here."

All of the instructors chime in, in unison, their voices weary with hard-won

experience: "We wouldn't say it if it wasn't important."

Finally, we are warned about ticks and their dreaded Lyme disease. We are to

check for the small black dots twice a day all over our bodies, particularly in

those dark, warm, hairy places ticks apparently love. A proper self-scrutiny is

demonstrated by one of the (clothed) volunteers, who takes to the stage holding

a small hand mirror from the shower stalls. He moves it over and around his

torso and limbs like a fan dancer, looking into the glass the whole time. As the

coup de grāce, he shows us how to check our least accessible, most unwelcome

potential Tick Hideout. Turning his back to us, he bends over, bringing the

mirror up between his legs. "Ta-da!" he says, holding a triumphantly

abject position. Everyone applauds.

WE MEET THE MAN HIMSELF the following morning in a welcome lecture of sorts.

Tom Brown is handsome and in great shape. With his silvering hair neatly parted

on the side, trim mustache, and penetrating blue eyes, he resembles nothing so

much as the scary, casually hostile, and emasculating gym teachers of my youth.

|

|

The mother hen of all drill sergeants: Author and teacher Tom Brown, hears

a tree calling his name. |

I'm only half right. Brown, while blessed with deadpan comic timing and a

Chautauqua preacher's instinct for the performative flourish, also exhibits a

disquieting and ever-present bass note of dwindling patience. This weird duality

is an acknowledged fact. Kevin has warned us that Brown is "part mother

hen, part drill sergeant." For the uninitiated, it can make for a fairly

bizarre ride, sometimes in the same sentence. He begins with a little flattery,

praising our very presence.

"The terms 'family' and 'brother- and sisterhood' do not fall flippantly

from our lips."

That's nice, we think, prematurely warmed to our cores.

He continues. "Even my parents—when they call, the calls are screened.

I talk to them when I want to. But you," he indicates us, snapping back to

sweetness, "you speak my language. When I say to one of you, 'Hey, I heard

a tree call your name,' you'll know what I mean. You're more than eight-to-five.

I'm an alien out there," he says, meaning society. "But not with you.

You're the warriors."

Happily, the Standard Class is not boot camp. We are not hiked miles and

miles, made to gather firewood for hours on end, or required to test our

physical mettle in any appreciable way. It's more intellectually rigorous. The

days are long, from six in the morning to past 11 at night, largely spent in

lecture, with hands-on experience making up only about 20 percent of our time.

During breaks—primarily the time set aside for meals—we practice our skills.

The yard outside the barn buzzes with pre-industrial activity: people making

cordage, lobbing their throwing sticks at a shooting gallery of plush-toy prey,

fox-walking and stalking slowly across the grass, and trying to start fires with

bowdrills.

This last one is our primary milestone. The squeak of turning spindles and

the sweet smell of smoldering cedar, occasionally followed by the applause of

whatever small group might be standing nearby, is a constant. I make three

attempts before success—but when it comes! The thrill of sawing the drill back

and forth, watching the accumulation of heated sawdust, now brown turning to

black, the thin plume that rises, the gentle coaxing of the tiny coal into

fragile, orange life, the parental swaddling of that ember into a downy tinder

bundle, the ardent, almost amorous gentle blowing of air into same, the curling

smoke, and the final, brilliant burst into flames in one's fingers—its

atavistic high simply cannot be overstated.

Recapturing and maintaining a sense of wonder is at the very heart of the

Tracker School philosophy, which is in part "to see the world through

Grandfather's eyes." In other words, in a state of complete awareness,

living in perfect harmony with nature, attuned to what is known in the Apache

tradition as The Spirit That Moves Through All Things. This awareness will

provide the key to tracking animals, both human and otherwise. "Grandfather

didn't have two separate words for 'awareness' and 'tracking,'" Brown tells

us one morning.

No doubt. But Brown's subsequent description of a brief, hundred-yard morning

walk from his house to the barn is so strange and omniscient, he calls to mind

Luther and Johnny Htoo, the chain-smoking 12-year-old identical twin leaders of

the Karen people's insurgency movement in Burma, with their claims of

invisibility and imperviousness to bullets: "There had been a fox. The

hunting had not gone well. She emerged at 2:22 a.m. Her left ear twitches.

Another step, now fear, and suddenly the feral cat appears. She's gone!" We

won't be able to reach this level by week's end, but apparently, we are told

frequently by both Brown and the instructors, we will be able to "track a

mouse across a gravel driveway."

"FULL SURVIVAL," in Tom Brown's world, has nothing to

do with the amassing of alarming quantities of canned food, a belief that the

government is controlled by Hollywood's Jewish power elite, home schooling, CBS

reality-based programming, or Charlton Heston. Full survival means naked in the

wilderness: no clothes, no tools, no matches. It is both worst-case scenario and

ultimate fantasy. Worst case being that the End Days have come upon us, the

skies bleed red, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse have torn up the flower

beds, and we must fend for ourselves and our loved ones. The fantasy being that

we've gotten so sick and tired of our consumer society that we just park our

cars by the side of the highway, step into the woods, and disappear. An

oft-repeated joke throughout the week is, "Next Monday, when you go in to

work and quit your jobs..."

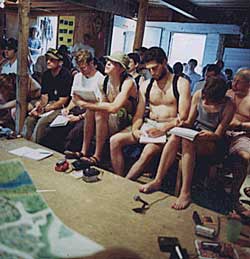

|

Class in session in the barn |

Being in the woods, we are told, will become an experience akin to being

locked in the Safeway overnight. "The main danger in full survival is

gaining weight," Kevin avers. Nature is a bounteous paradise for those who

play by the rules. That would be nature's rules, not the government's. Since

much of the nation's remaining wilderness falls under the protective

jurisdiction of the National Park Service—whose rangers don't look kindly on

the wanton building of debris huts, and killing and eating the animals—much of

what we learn turns out to be illegal in what remains of wild nature.

Case in point: animal skinning. Even picking up roadkill requires a permit.

On Tuesday evening, for the lecture on skinning and brain-tanning, Ruth Ann

comes in wearing a fringed buckskin dress that she made herself. She tells us

the story of coming upon a roadkill buck while taking a much-needed break from

writing college papers. My immediate reaction the entire week to anything Ruth

Ann tells me is eagerness and a wish to try whatever it is she is proposing.

When she tells us how to slit the animal down the middle, and then to cut around

the anus and genitals, and then to pull them through from inside the body

cavity, I think, regretfully, "I wish I had a dead animal's anus and

genitals to cut around and pull through its body cavity."

I almost get my wish. She dons a pair of rubber gloves, leaves the barn, and

comes back bearing a very dead road-killed groundhog. It has already been gutted

and the fur pulled down from the hind legs to just below the rib cage. She hangs

it on a nail by its Achilles tendons. Grabbing hold of the pelt, instructor Tom

McElroy—the Kid—pulls, using his entire body weight. Groundhogs, as it turns

out, have a great deal of connective tissue. There is a ripping, Velcro-like

sound as the fur comes down. McElroy briefly loses his grip and the wet animal

jerks on its nail, spraying students in the front row with droplets of

groundhoggy fluid. The bat flutters around the barn throughout.

Next comes the tanning. Almost nothing is better at turning rawhide into

supple leather than the lipids in an animal's own brain, worked into the skin

like finger paint. A further, utterly beautiful economy of nature is the fact

that every single animal has just enough brains to tan its own hide. Ruth Ann

made her own wedding dress from unsmoked buckskin, as well as her husband's

wedding shirt. She has brought them to the lecture to show us. I expect her to

look rough-hewn, disinhibited, and slightly tacky—like Cher—but when she

takes the dress out of the box and holds it up against herself, it is lovely:

soft, ivory, and impeccably constructed. My crush is total.

But there will be time for infatuation tomorrow. It is getting late, and as

happens every night, my ragestarts to set in around 10:45 when people refuse to

stop asking questions. I'm desperate to get to bed, having concluded my

approximately two and a half hours' worth of obsessively running to the can

during breaks—prophylaxis against a groggy stumble through Tent City to the

Porta-Johns in the middle of the freezing-cold night. A small cadre of exhausted

fugitives has already disappeared, heading back to their tents slowly and

silently, without flashlights. I join them.

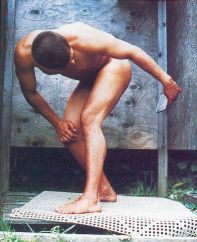

|

A twice-daily tick check is recommended |

AWARENESS STARTS small. Only when we understand the many

mysteries that lie within the earth's tiniest, seemingly mundane details will we

be able to track animals or people. "Awareness is the doorway to the

spirit, but survival is the doorway to the earth. If you can't survive out there

naked and alone, then you're an alien," Brown says one morning, gaining

volume as he goes. "You think the earth is going to talk to someone who is

not one of her children?" he yells.

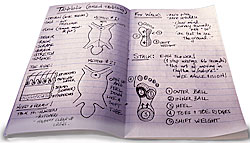

|

Not a pampering school: The conscientious author took 150 pages of notes

during lectures. |

My guess is no. To that end, we are taken out to a meadow overgrown with

heavy grasses, garlic mustard, and wild burdock, a place known as Vole City for

its large population of small rodents. We each lie down and examine an area no

larger than a square foot, digging down, exploring.

My classmates look very idyllic and French Impressionist, scattered about

here and there, supine in the sunlight, lost in contemplative investigation.

Myself, I sit up, terrified at the prospect of finding anything, especially a

vole. The instructorshows me how to root around just underneath the grass to

find their ruts. I use a stick to gingerly push aside the stalks and turn over

the debris, picking out the dull sheen of a slug here, the progress of a tiny

worm there. Thankfully, no voles. Warming to my task, I suddenly spy—dark,

wet, and gray against the fresh green of a blade of grass—the unmistakable

articulation of amphibian digits, a hand span no bigger than this semicolon; it

is connected to a tiny amphibian arm, connected to a tapered amphibian head the

size of a peppercorn. The gleaming, dead eye catches the sunlight. My heart in

my mouth, I call the instructor back over and show him. He picks up the tiny

sprig with the half-eaten salamander still perched on it and holds it four

inches from his mouth, enumerating the various classifications of the creature:

the coloring, the reticulations, the patterns, the species. The instructor

tries, God bless him, to draw me into a Socratic dialogue, asking me questions

about what I've observed. He points to the chewed-out underside of the demi-lizard.

"What kind of teeth marks made those cuts? Are the edges scalloped? Look at

the gnaw marks. That's a great find," he concludes, patting me on the back.

I show my salamander to those working near me in the field, and they show me

what they've uncovered. I feign interest in one woman's small mound of

unidentifiable animal scat. But we both know the truth: My corpse makes her find

look like, well, a pile of shit. For a brief moment, I am Big Man in Vole City.

The instructor's matter-of-fact treatment of the dead salamander, the

complete lack of any "poor little guy" moral component to its demise,

speaks to what makes the Tracker philosophy unique. There is none of that

falsely benign conception of nature as friendly, inherently good, tame, and

prettified. Aldous Huxley, in his essay "Wordsworth in the Tropics,"

assails what he calls the Anglicanization of nature, the cozy revisionism of a

force that is intrinsically alien and inhospitable: "It is fear of the

labyrinthine flux and complexity of phenomena...fear of the complex reality

driving [us] to invent a simpler, more manageable, and, therefore, consoling

fiction."

At Tom Brown's Tracker School, there is a clear-eyed acknowledgment that

things eat and get eaten. Ruth Ann, in telling us of the year she lived in the

Pine Barrens in a house she made entirely by hand with cedar walls and a debris

roof, gets straight to the point. "Whatever came into my house, I

ate," she says. "Mice? We just threw 'em in the fire, burned the hair

off, and ate them whole. They just taste like meat, and there's something to be

said for that added crunch."

She's not being heartless; in fact, she's the very opposite. For every skill

we are taught, whether it's harvesting plants, using our bowdrills, skinning an

animal, or gathering forest debris, the first step in our instruction is always

a moment of thanksgiving for the trees, the spirit of fire, the groundhog, the

water. It's a strange adjustment to have to make, at first. I am not proud to

admit that there was a moment at 5:30 a.m. on the fourth day of class when,

serving on cook crew, I stood bleary-eyed with exhaustion—having only gotten

to bed some five hours earlier because of a late-night lecture on wild

edibles—and seriously considered killing the guy who led us in a 15-minute

thanksgiving that included complimenting the rising sun for being "just the

perfect distance away from us."There are worse things than acknowledging a

continuum and connection between all things and staying mindful and grateful of

our place therein, but it can be a hard concept to swallow before the coffee

hits the system.

Even wide awake there are moments of fuzzy logic in this theory of

interconnectivity. Kevin, our elder statesman, explains that the Apache

tradition of being thankful to the prey will also result in a willing

acquiescence on the part of the hunted. "Something that gives its life for

your benefit does so with gladness, if you are humble," he intones. Isn't

it pretty to think so. Ascribing complicit suicidal motives to the rabbit who

licks the peanut butter from a deadfall bait stick—no matter how

self-effacingly daubed on—seems a tad Wordsworthian to me.

But such doubts become ever fewer as the week progresses. From about Thursday

on, the home stretch of the course, spirits are high. Most of us have gotten

fire, and in a brilliant bit of Pavlovian pedagogy, the food improved markedly

after the outdoor cooking demonstration. Despite the staff's urging us not to

take what we are told at face value, to go home and prove them right or prove

them wrong, we're all pretty jazzed and itching to head out into nature. That

said, among the people I talk to there is also a growing skepticism about Brown

himself. It has nothing to do with his credibility, the veracity of his life

story, or even the purity of purpose of the Tracker School. Unfortunately, it's

personal: Brown's drill sergeant persona thoroughly throttles his mother hen. As

pleasant as he may be just after breakfast—and he frequently is sunny,

sprightly, and very funny—if he addresses us after sunset, there is a darkness

in him and a potential for ire that is frankly terrifying.

In one evening lecture, he talks about the necessity for us to "take

bigger pictures," to see more of the world through our wide-angle vision,

to sense things before actually seeing them. "Instead of going click,

click, click," he minces, "go CLICK! CLICK! CLICK!" he suddenly

roars. A few people actually flinch. Later on, in a moment meant to chide us for

the persistence of our citified tunnel vision, he tells us that he has been

observing us unseen from a perch on top of the tool shed. As we make our way to

bed, we watch our backs, scanning our surroundings for heretofore unnoticed

surveillance. One young man asks the group softly, "You guys ever see Apocalypse

Now?"

IT'S TOO BAD THAT Brown the Personage has this effect on some

people, because when I interview Brown the Person on Friday afternoon, the

next-to-last day of class, he turns out to be a nice, intelligent guy with an

undeniably noble and admirable mission in life. "It would be my dream to go

back into the bush and live and never have to face another aspect of

society," he tells me as we sit at the kitchen table in front of a stone

fireplace. "But that's not my vision, that's my dream. My vision is to

reach as many people as I possibly can." Still, he remains adamant about

not franchising the Tracker School despite huge enrollment. (Before Standard

Classes swelled to close to 100 people, the waiting list was six years.)

By the time I meet him, though, my disenchantment has become fairly

entrenched. It doesn't help that Kevin escorts me into the modest house that

Brown shares with his second wife, Debbie, 33, and their two young

children—and doesn't leave, joining Tom McElroy, who is sitting in a chair,

weaving a jute bag on a small circular loom. They crack jokes, weigh in with

opinions, engage in quiet conversations with one another; the phone rings; they

pour themselves coffee. Pretty soon I realize I've come to the teacher's lounge.

Or is it a convocation of disciples? I ask Brown about the cult of

personality that seems to be part of the Standard Class.

"Oh, I try to get rid of that real quick," he says. "I tell

people right off, 'Don't thank me, thank Grandfather.' I'm a poor example. I am

nobody's guru." Brown talks about how he, Kevin, Ruth Ann, and the crew

have to make sure to keep "Tracker groupies"—those over-enthusiastic

few who try to volunteer just a little too often—at a healthy distance.

"Boy, this would be very easy to turn into a cult, big-time," he

admits, "and I just will not allow it to happen. That's the last thing I

want to happen."

Noted. And yet, in almost every lecture, there is the requisite prefatory

story from Brown's life: "When Tom was 12 years old, Grandfather told him,

'This is the year you will provide me with meat...'" The accrual of

personal detail forms a gospel of sorts, and anecdotes are delivered in a

hortatory, liturgical style. Granted, the stories are told to show the wisdom of

Stalking Wolf, not Tom Brown, but the reflected glory of playing Boswell to

Grandfather's Johnson (a term straight out of a traveling salesman joke) clearly

has its attractions.

Attractions not callously exploited, it seems. There is no line of Tom Brown

sportswear, no exhortation from Brown that I buy anything while I am there, that

I "Think Different." At a very manageable 600 bucks for a week of food

and instruction, the Tracker School is not the enterprise of the career

opportunist. In person, Brown is not only not power-mad, but he comes

across as almost as nice as one of his instructors.

I leave the house fairly won over. I return to Tent City and walk out into

the field to gaze at the sun, now lowering in the late afternoon sky. I find one

of my classmates standing in the grass in the honeyed light, enjoying a water

bottle full of herbal tea. We stand there amiably and peacefully, mutually

imbued with the soy milk of human kindness. He holds out the bottle of amber

liquid, offering it to me, and says, "Rum?"

OUR LAST SUPPER is one of our own harvesting. I'm on burdock detail, digging

the rough, brown, footlong roots out of the red clay of a nearby field with a

fellow student. Back at the cooking shed in the main yard, all 90of us spend an

hour or so cleaning, scraping, and slicing. I have never had a meal so Edenic in

its profusion and beauty: a salad of chickweed, violet flowers, pennycress, and

wild onions; a stir-fry of burdock, dandelion, nettles, and wintercress buds;

dandelion flower fritters; garlic mustard pesto over whole-wheat pasta

(store-bought—cut us some slack); nettle soup; and spicebush tea. We are each

given a trout to gut, wrap in burdock leaves, and place in the fire. After six

days here, I approach this task with a strange relish. It is the best fish I

have ever eaten.

The grand finale of the Standard is a nighttime sweat lodge. I generally try

to avoid pitch-dark, infernally hot enclosures, but now that Brown is my new

best friend I find his preamble so avuncular and sweet that I almost consider

it. He tells us we are to enter in a clockwise direction, leaving the area

behind him free for those among us who suffer claustrophobia. "The minute

you want to get out, just say so and we'll open the doors," he proclaims.

"I won't love you any less."

I resolve to do it until he cedes the floor to Joe Lau, the ninjutsu expert,

who reads us the guidelines. When I hear "crawl in on your hands and

knees," I realize that there is not Xanax enough in the world to make me

enter the low, round, straw-covered structure. The other rules include taking

off all metal jewelry that doesn't sit directly against your skin as it can heat

up, swing back, and burn you pretty badly. And then there's the final

admonition: "You are absolutely forbidden to pass wind in the sweat

lodge," says Joe. "We wouldn't say it if it wasn't important."

The students assemble in their bathing suits, and there is something strange

and primal about this nearly naked crowd in the moonlight. Their progress into

the lodge is slow, and it takes a while for everyone to crawl in. I can hear

Brown beginning his incantatory singing.

I rise early on the last morning. I'm almost the only student awake. I ask if

there's anything I can do, and one of the volunteers asks me to build up the

fire. "Well, how the hell am I supposed to do that?" I think to

myself. Almost as quickly, I realize I know precisely how to do that, and much

more. I have never taken in more information in one week in my life. Can I track

a mouse across a gravel driveway? I couldn't track a mouse across a cookie sheet

spread with peanut butter, but that's no matter. Despite Kevin's recantation in

his final wrap-up, when he begs us, "Don't quit your jobs, don't

make any radical decisions for the next three months, don't trash your

relationships..." ("How many of us did that?" Ruth Ann

stage-whispers), I can't help feeling like I could if I needed to, and survive.

Lavishly.

Another student gives me a lift to the bus station. I count the roadkills on

the shoulder of the highway along the way. "I could do something with

that," I think. "And that. And that." I resist the temptation to

ask my driver to pull over and let me out, so that I may part the trees and step

through, letting the branches close behind me as I keep walking, until I can no

longer be seen from the road.

Reproduced from

http://web.outsideonline.com/magazine/200010/200010natureboy1.html

Copyright Outdoor Magazine (Mariah Media Inc.) |