|

|

|

|

|

Home →

Publications →

In the News

|

|

|

|

Secrets to Survival

Backpacker Magazine - October 1992

Larry Rice

|

|

|

|

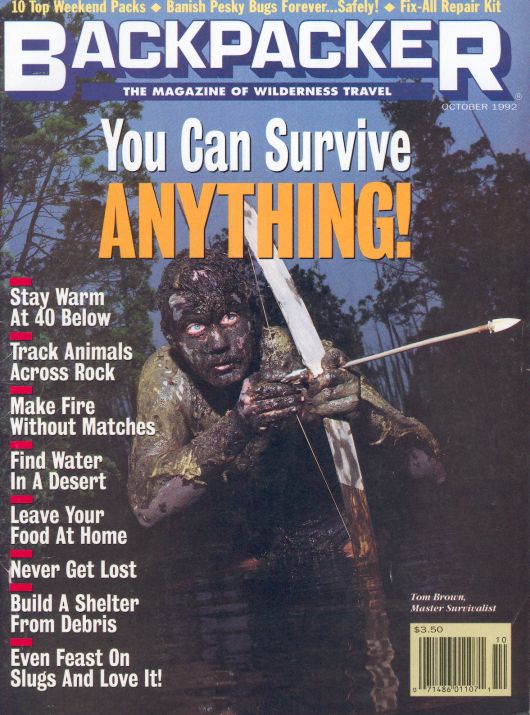

Front Cover |

|

|

|

|

|

Table of Contents Page |

|

|

|

|

|

In the world according to Tom Brown,

everything you need to stay alive is in the wilderness. |

|

|

|

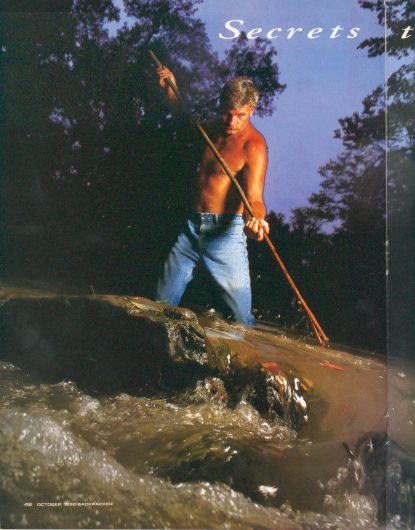

Tom Brown fishes with a handmade spear in a

tributary of the North branch River, New Jersey. He says the

primitive technique, which mimics the slow, deliberate movements

of a hungry heron, is "easier than line fishing." |

|

|

|

|

The teacher's first words to his attentive pupils stiffened

every spine in the old barn-turned classroom: "It's going to be one

helluva grueling week, I kid you not. I don't believe in free time when

you're on a course like this. I'm not some gray-haired old guru, and we

don't sit and jabber under an old oak tree."

The speaker is Tom Brown Jr, the infamous

"Tracker," operator of the nation's largest wilderness survival

school, and author of a best-selling library of field guides built around

his experiences and knowledge of staying alive in the outdoors. (The

Tracker was his first and probably most widely read book.) Perched on

too-hard wooden benches, listening intently, are 43 students, ages 15 to

65, from all over the United States. We are computer programmers, business

executives, park rangers, mountain guides, college students, artists and

aspiring actresses, and we have gathered at Brown's rural dairy farm in

Warren County, New Jersey for one purpose: to learn to survive in the

wilderness using only our wits and what nature provides.

Pacing back and forth with restrained energy, Brown, 41, is

intense. His clear blue eyes stare straight ahead, wilting subjects of

lesser fortitude. He's 6'2", 200 pounds and moves with the grace of a

Tai-Chi master. This is the man who teaches Navy Seals escape and evasion

tactics, who has been shot four times during law enforcement searches, and

has pulled more than 160 bodies out of the woods -- most of them dead from

lack of survival skills, and the others just plain criminals. A forceful

speaker and inspired teacher, Brown is impassioned and unequivocally sure

of himself. |

|

|

|

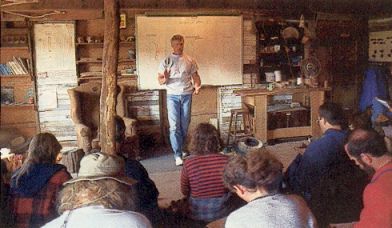

Much of the Tracker's beginner course

involves classroom lecture. Once equipped with the knowledge of

survival basics, students head out to the Pine Barrens to

practice the skills. |

|

|

|

|

All first-timers to the Tracker School complete the

beginner's course before tackling the more technical, physically demanding

advanced classes. In the coming days, we neophytes will learn nature

observation, tracking, survival, and Native American lifestyles and

philosophies. Brown says by week's end we'll be able to survive in the

wilderness without any traditional backpacking equipment, know more about

nature than we ever thought possible, and be able to track a mouse across

a cement floor. For the skeptics in the class, Brown backs up his claim

with a money-back guarantee, adding, "I've never had to refund any

money yet."

It's not that I question Brown's wisdom and abilities,

because to do so would be premature and narrow minded. Besides, who wants

to piss this guy off? But some of the things Brown says during the seven

days are incredible (read: hard to believe). Then again, it's fair to say

that Brown's life has been incredible (read: hard to believe), almost like

a Hollywood screenplay. So much so that he has been approached by movie

bigwigs and television producers.

Toms River, New Jersey, may seem an improbable locale to

learn the art of tracking and survival, but it was here, when Brown was

seven years old; that he fell under the influence of his best friend's

grandfather, an 83-year-old Apache medicine man named Stalking Wolf. For

10 years Stalking Wolf acted as the boys' mentor, teaching them the ways

of the Apache, as well as his own wilderness survival skills. Every day

after school and on weekends, the boys accompanied Grandfather, as they

called him, along the maze of sand trails threading through the swamps and

scrub trees known as the New Jersey Pine Barrens. These were no ordinary

camping trips, no Boy Scout outings. They were serious, often difficult

lessons involving survival, tracking, nature awareness, and ancient

philosophies of the Earth. "Apache scouts were superb

survivalists," Brown says, staring out the open window into a

corn-stubble field farmed by his neighbor. "They were mobile, their

awareness was second to none, they were legendary trackers, and

Grandfather was one of the best."

Initially, communication between Brown and

Grandfather was labored. There were differences in language (Grandfather

spoke little English) as well as culture, but slowly the gaps were

spanned. Brown became obsessed with learning the old ways.

"Grandfather was a 'coyote

teacher'," Brown explains, pausing briefly as several students change

cassettes in tape-recorders placed on the wooden platform up front.

"A coyote teacher would never answer your questions

directly. He would ask you another question or point you in a direction.

For example, when I asked Grandfather how to track, he said, 'Go ask the

mice'."

And that's what Brown did. For six months, whenever he had a

spare moment, Brown examined the minute tracks and droppings of voles,

mouse-like rodents common to the Pine Barrens. "My knees were

callused like the soles of old shoes from so much crawling around, but it

was a great education. Studying voles, doing dirt time on my belly, taught

me more about nature and tracking than all of the field books combined.

That's coyote teaching."

When Stalking Wolf died in 1970, Brown's apprenticeship ended

and his journeyman phase began. By this time, Brown admits he was a

"social misfit," preferring the company of animals to people,

and wilderness to civilization. He headed for the woods and the mountains

-- Yosemite, Death Valley, the Grand Canyon, Montana's Bob Marshall

Wilderness. His travels lasted nearly 10 years, during which time he used

no industrially-manufactured tool or product, preferring instead to live

off the land, honing his skills as a tracker, following Stalking Wolf's

teachings.

Brown was frightened when he walked out of

the wilderness in the late 1970s and returned to New Jersey. "Things

scared me about our Earth, primarily people's lack of spirituality and

awareness. They felt nothing, saw nothing, walked around like zombies. We

are a society of robots, our lives geared by clocks." Searching for a

niche was a daunting task for Brown. Friends and family asked why he

wasn't in college, why he didn't have a 9-to-5 job, why he wasted so much

time running around the Pine Barrens. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brown's reputation as a tracker caught the attention of law

enforcement and rescue agencies. At first, police were skeptical, but in

nearly every instance, Brown says without modesty, he found his quarry

when hundreds of searchers, and even helicopters and dogs, could not. By

the age of 28, he'd found 40 missing persons and helped investigate four

murders. Minor celebrity status followed. Tom Brokaw interviewed him on

"The Today Show," and he was featured in People magazine. In

1978 a book about Brown's youth, The Tracker, was published and a

condensed version appeared in Reader's Digest, with a blurb at the end of

the article stating Brown was in the Pine Barrens teaching survival

skills. In truth, he was merely hanging out with friends. As a result of

the article, a truckload of mail was waiting when he returned home, all

from people wanting information about his survival school-the one that

didn't exist.

Leery at first about putting down roots, let alone

establishing a business, it took serious soul-searching before he realized

that teaching people how to stay alive in the outdoors was the answer to

what he was looking for in life. By 1980, Brown was traveling coast to

coast teaching classes and three- and four-day seminars. The Tracker had

become incorporated.

Like anything new and unproven, Tracker, Inc. went through a

period of trial and error. Brown initially took students into the Pine

Barrens with only the clothes they were wearing and a knife. "All

they learned was how to suffer for two weeks," he candidly admits.

"They spent all their time foraging and keeping warm - a waste of

time."

This is the reason his beginner course (booked up to a year

in advance) is half lecture and half skills. "You need the basics

before you can master the skills. You can't go into the wilderness

unarmed. Then, in the advanced courses, we take you through the transition

from regular camping to full survival living. That's when you understand

that pain and survival are not synonymous."

According to Brandt Root, a New York City stock trader who

completed several of Brown's advanced courses, making it through the

Tracker's "life and death situations" and learning things like

"how to make a fire in 30 seconds" builds confidence. "I

can make the transition from city to wilderness without any equipment. I'm

planning a fishing trip to Montana or Wyoming and the only thing I'm going

to take is my fly rod. If the world came to an end tomorrow, I could

survive longer than most."

Many of his students are urban dwellers who are proud of

their survival knowledge, but can rarely practice their skills because of

family and career responsibilities. Brown is the same way. When someone in

our class asks when he last went into the wilderness alone, he wearily

replies, "Years ago. The Tom Brown in The Tracker is dead."

There is silence in the room as he lights another Marlboro, ignoring his

rule that smoking isn't permitted inside. "I don't want to be here. I

want to be in the mountains more than anything. I can taste it. But I

can't live my dream, I have to live my vision. The only thing I can do now

is teach and write. I am a very, very desperate man." |

|

|

|

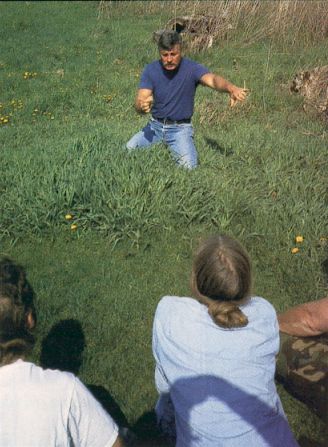

Brown demonstrates vole-tracking. He learned

how to track by spending hours of "dirt time" with the tiny

rodents, and he instructs his students to do the same. |

|

|

|

|

And here is where contradictions surface. He

teaches people how to live alone in the wilderness with nothing, but he

and his family live in a comfortable farmhouse complete with electricity,

running water, a VCR, even a home computer. When he goes to New York City

to meet with his publisher, Berkley Books, or his agent, he spends his

spare time tracking animals through Central Park. Although Brown longs to

be a wild man, he has a family to support, a business to run, books to

write, and a greater good to accomplish: "Earth Mother is running out

of time, but we can turn things around. That's the underlying reason I

have you here -- not so much to teach the skills, though they are the

doorsteps to the Earth, but to implore you to save the Earth. We have to

re-educate people to get back to the Earth, otherwise we are on borrowed

time."

For the better part of two days, both indoors

and in the field, Brown and his staff inundate our minds and notebooks

with the ancient art of tracking. "Tracks house a wealth of

information that escapes most people," Brown explains. "It's

like reading a topographic map. Everything going on in the animal's mind

and body is recorded in its track. Tracking is a window to the past --

looking into an animal's very soul."

While the beginners rarely get to see Brown's

legendary talents in action (no mouse tracking across cement), students of

the advanced classes have witnessed some amazing feats. During an advanced

tracking course, Brown spotted a coyote track 150 yards away. On that same

outing deep in the Pine Barrens, he casually pointed out raccoon tracks on

a tree 30 feet away.

We beginners are taught to mimic different

types of animal locomotion. To a casual onlooker, we are a bunch of

ridiculous adults hopping like rabbits, pacing like bears, and bounding

like weasels, all of which helps us grasp why animals leave a

characteristic track pattern. Next, we gather in an overgrown pasture,

where the remainder of the afternoon is spent belly-down in the grass

looking for vole scat and hair, and peering into tiny tunnel-shaped rodent

runways.

Although tracking with the Tracker is

intriguing, the big draw for many of Brown's students is learning how to

survive the "what if" situation. What if I get lost in the

woods? What if I capsize my canoe and I lose all my supplies? "When

you leave this school you won't have that nagging question," Brown

says at the start of his survival lecture. "You'll carry that

backpack into the wilderness, but you will not need it."

For the New York City stock trader, Brown's

teachings have indeed proven useful in the back country. "One time a

friend and I were canoeing. We were really out there when I realized we'd

forgotten the tent. I just fixed up a debris hut for two and it worked

fine. When you're not worried about things like getting lost or leaving

your tent, you enjoy the wilderness much more." Which is why Brown

stresses that the most important survival tool sits on your neck.

"Your mental attitude, your mind, will make or break you -- it's all

a matter of choice. If you're freezing, don't ask why you're cold. Ask

what can you do to get warm?"

Wilderness survival depends on maintaining

priorities, the most important being shelter, since most deaths are from

exposure to heat and/or cold. According to Brown, there's just one

approved shelter: the debris hut, an envelope-like nest of brush, leaves,

grass, and, that's right, debris that holds one person, maybe two. It's

the perfect natural sleeping chamber because it traps and holds heat,

which is probably why it's so popular with primitive cultures. On advanced

courses, students wearing little or no clothes have field-tested debris

huts in temperatures of -40°F, and have reported being too warm.

We learn how to gather water (the common grapevine, when

sliced, is a veritable garden hose); make arrows, and start a fire with a

bow and drill (I'll never take my Bic for granted again). Fifteen-hour

work days are the rule, not the exception. The most enjoyable session,

simply because it's the most relaxed, is imitating Euell Gibbons and

foraging for edible wild plants.

Brown dismisses the moral concerns raised by vegetarians when

we move on to hunting and trapping. "In full survival conditions,

especially in winter, you cannot survive on plants alone. You must hunt

and trap. Anything finned, furred, feathered or scaled is fair game."

We fashion sinister-looking snares and deadfalls, and practice throwing a

baton-like "rabbit stick," Brown's weapon of choice in a

survival situation.

But to kill a deer, or any animal, with a stick, you have to

be within striking distance, and that's where stalking comes in.

"Native Americans were close-range hunters. The mark of a good hunter

was how close he could get." To stalk means to move very slowly.

Grandfather taught Brown how to stalk by having him "fox walk"

barefoot on sharp stones. "With the fox walk," Brown

demonstrates, "you no longer move your head. You move from your

center. Your toes are pointed straight ahead. No weight is committed until

you know what you're stepping on. You have eyes in your feet. You no

longer have to look at the ground."

Brown slips into an imaginary stalk.

Semi-crouched with barely any discernible movement in each of his steps,

he resembles a cat moving stealthily toward an unsuspecting prey. In the

eyes of a deer, he would be part of the forest's tapestry. "After you

learn how to fox walk," Brown says, breaking out of the stalk,

"you'll be amazed at how many animals you'll see."

Graduation day finds us back in the old barn

for our final lecture. It is a wrap-up of all the things we've learned and

are still trying to absorb. I've filled a 100-page notebook -- that's more

notes than I took during an entire semester of biology. Brown cautions

that it will be a while before everything starts falling into place.

"Your real education will begin when you get home and enter the woods

on your own."

Forty-three pairs of eyes focus on Brown as

he gives us his last bit of advice. "When Native Americans would take

leave of each other, they wouldn't say goodbye because goodbyes were

final. They would simply turn and just walk away," which is what the

Tracker does. |

|

|

|

|

|

This website has no official or

informal connection to the Tracker School or Tom Brown Jr. whatsoever |

|

|

|

|